LESSONS FROM THE PAST FOR A CHALLENGING FUTURE

Alain Bifani, Karim Daher,

Lydia Assouad, and Ishac Diwan

Introduction

The goal of this paper is to evaluate the Lebanese tax system, and to make considerate proposals to make it more inclusive and efficient. That a topic of this level of technicality has come to command interest is a testimony of the intellectual impact of the October 17 uprising, which has initiated a search for just and effective solutions to the current crisis, as well as a rethink of how to organize the economy to put it onto a path of sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

The discussion about the needed reforms is grounded in the deficiencies of the existing tax system. There are two related challenges. First, reducing the fiscal deficit and stabilizing the macro-economy is a precondition for future growth. We cannot emphasize enough that the fiscal dimension needs to be part of a broader and credible adjustment program, and it needs to be accompanied with political reforms that generate sufficient trust in government before taxation can be increased. But equally, a more effective and just fiscal system is also at the heart of any vision for a “new Lebanon”, in which public spending needs to be reorganized to allow the state to be able to deliver the type of social and infrastructure services that can allow for more social mobility and higher labor productivity.

The tax system is at the heart of both short- and long-term challenges. The ineffective current system – with its narrow base, large holes, and deep regressivity, requires major reforms. Increasing tax revenues over time, while supporting a more inclusive and productive society, requires a rebalancing of the tax structure to make it fairer, strengthening tax compliance, and broadening the tax base. It also requires replacing the multiple exemptions serving rent-seeking motives by targeted ones serving the public good. More fundamentally, it requires strengthening the values of integrity and tax citizenship. New challenges include finding ways to build international alliances to reduce tax avoidance.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 takes a bird’s eye view at the tax system in Lebanon. Section 3 focuses on the adjustments needed in the short term, in support of a stabilization plan. Section 4 looks into medium term changes needed to increase the size and fairness of revenues. Section 5 focuses on the exemption regime, and section 6 on tax administration. Section 7 concludes.

2.TAX STRUCTURE AND INEQUALITY:

Insufficient, un-equalizing, and leaky

The tax system in Lebanon does not raise sufficient revenue and is unfair and leaky. In this section, we document its basic structure and compare it to that of other countries.

Size of revenues

Lebanon has a low level of tax revenues at about 15% of GDP in 2018 – similar to that of Senegal and Costa Rica, but lower than the average of all developing regions – including Sub-Saharan African (17%), the MENA oil-importers (18% ), and Latin America (23%). In the region, its tax revenue to GDP ratio is closest to that of much poorer Egypt (16.7%), but way below countries that are marginally poorer, such as Morocco (27.8%) or Tunisia (32.6%) – see Figure 1 and Table 2. The low level of fiscal revenue means that the country is unable, unless the system is reformed, to finance effective social policies and deliver basic public goods and services.1

Post-civil war, the tax system undertook several waves of mini reforms, mostly pushed by the administration against politicians’ will. The first important change was the introduction of a value added tax (VAT) in 2002. A second wave introduced taxes on

capital: in 2003, a tax on interest earnings was introduced – initially at 5%, then raised to 7% in 2017, and now temporarily set at 10% (for 2020-22); in 2017, a tax on real estate capital gains (by individuals) was introduced with a maximum rate of 15%, and the corporate income tax was raised from 15% to 17%. In 2019, the rate for top incomes was raised from 20 to 25%.

Starting from a low base of about 13% GDP in 2000, tax revenues rose fast from 2000 to 2010, with the introduction of the VAT and the fast growth of the economy to reach 17% GDP (see Figure 2). Revenues declined with the collapse of growth post 2011, reaching 13% GDP by 2015. The fall was exacerbated by the reduced customs revenues related to the trade agreement with the European Union, and also, with the increased weakening of border control after 2011. There was a progressive recovery back to 15% of GDP by 2018, as new taxes got introduced, and tax efforts started to improve, especially in the collection of income and profit taxes.

In addition to straightforward tax revenues, other revenues add up to another 5% GDP on average, and they come largely from the state-owned telecom sector’s profits and taxes on telecom services.

The tax system is un-equalizing

Most developing countries rely largely on indirect taxation, which is easier to collect that income tax. But as apparent below, the system in Lebanon is excessively regressive, even when compared to that of poor and unequal countries, unfairly hitting the middle class and the poor and with very little incidence on the rich.

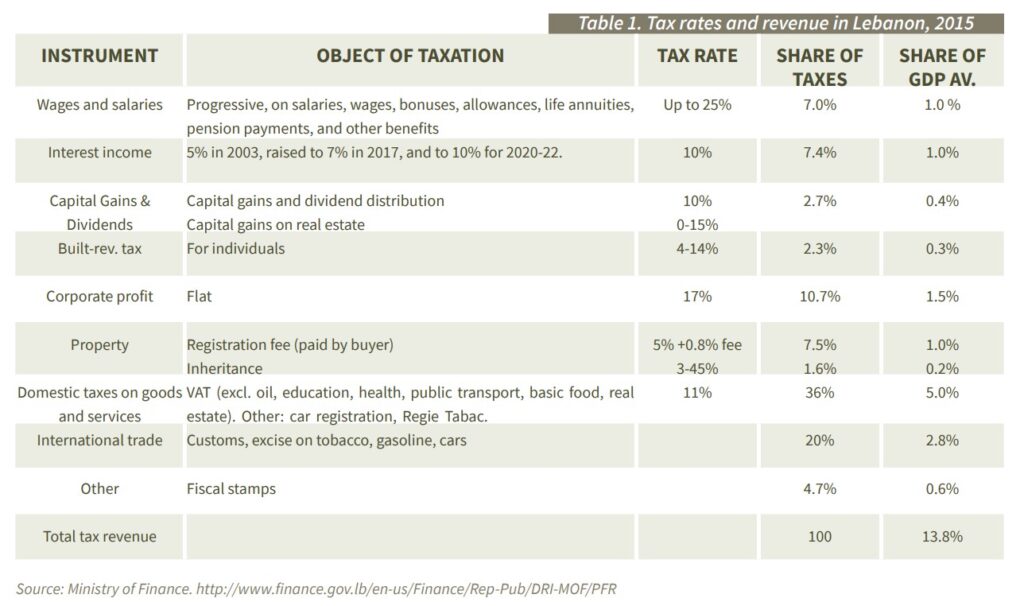

The system relies heavily on indirect taxation—value-added taxes, excise taxes, and tariffs added up to 56% percent of total revenues in 2015 (see Table 1), and together, they raised 7.8% GDP in 2015.2 Indirect taxes are notoriously regressive – even though the exclusion of basic necessities from the VAT (oil, education, health, public transport, and basic foods) reduces this to some extent, as is typically the case in other countries.3 Indirect taxes represent a much larger proportion of revenues than in the OECD, but a similar share as in Tunisia, Turkey, and Egypt – see Table 2, which contains information on a broad set of countries to which Lebanon can be compared.

But where Lebanon stands out is the very low share of revenues collected through a progressive scheme – only around 11%. This is because only wages, property income, and inheritance are taxed at progressive rates; the rates are still not very progressive (despite the latest increase in 2019 for the top incomes from 20 to 25%); and firms’ profit (which include the income of licensed professionals and one person businesses), interest earning, and capital gains and dividends are taxed at flat rates. The share of progressive taxes in comparator countries is 2 to 3 times higher, as both their income and corporate tax rates tend to be higher and more progressive (Table 2).

The taxation of personal income in Lebanon is based on an archaic system where each source is taxed separately – and wages, and income from interest revenues, dividends, property rental, and capital gains are each taxed at a separate rate:

- Labor income is taxed progressively, with the top rate at 25%.

- Income from rental of property is also taxed at a progressive rate (4 to 14%).

- The other income categories – mostly capital incomes, which usually accrue to the richest – are taxed at flat rates. Interest income, dividends, and capital gains are taxed at 10%. Since 2018, capital gains taxes also apply to sales of property by individuals, at a maximum 15% rate (the tax base decreases by 8% for each year the property was held).

The total of all taxes on various types of income amounts to 2.7% GDP (Table 1), much less than among the comparator countries – see Table 2. An important reason for this is the fragmentation of the system: by taxing each source of income separately, individuals with multiple sources of income get under-taxed – a progressive tax system on the whole of income would raise larger revenues from richer taxpayers by pushing them into higher income brackets.

The second part of direct taxation concerns corporate incomes. The tax on corporate profit is set at a flat rate of 17%. The rate is relatively low by both historical and international standards. This reflects the post-war political choice of a very liberal economic outlook, which was encouraged by the fall in rates around the world.6 The tax represents 11% of total revenues, at about 1.5% GDP. Egypt and Morocco for example derive a larger share of revenue from taxing firms, while Tunisia and Turkey are like Lebanon closer to OECD standards. But again, all these countries end up with larger revenues (twice in Tunisia for example).

Inheritance (and gift) tax rates are progressive, and vary between from 3 to 45%, depending on the relationship between deceased (donor) and heirs (recipient), and of the amount transferred (after deduction of exemptions applicable to estate beneficiaries and a fixed tax of 5 per thousand payable first by all heirs).7 The total revenue is low at a 0.2% of GDP.

There is a (flat) fee to register real estate properties – which is taxed at 5% of the value of the property (paid by the buyer), to which is added various administrative fees amounting to 0.80%.8 This tax raises 1% GDP and adds up to 7.5% of revenues. While the profit from land sales is now taxed at progressive rates, the registration fee is not progressive, introducing an extra element of regressivity in taxing capital.

Finally, it is worth noting here that there are no taxes in Lebanon that favor the public good, such as reducing pollution, improving the environment, or attracting growth opportunities to poorer regions, as is common in many countries.

A leaky system

While tax rates are in general low in Lebanon, at least relative to our comparator countries, tax revenues are much lower than in these same comparators because the system is very leaky. Overall, we estimate that if taxes were properly collected, tax revenues could increase by about 50% (or 6-8% GDP, see below). In particular, the collection of taxes at the border, of income taxes, and of the inheritance tax stand out as particularly ineffective.

The VAT is largely collected at the border (75%). The VAT compliance gap has been estimated by the MoF at about 3.3% GDP. MoF also estimates that lost custom revenue at the border in 2013 was about 1% GDP. Stricter border control could thus potentially raise VAT and customs revenue by 3-4% GDP.

The banking secrecy law has made it especially difficult to tax revenue among the “liberal professions” (engineers, architects, doctors, lawyers…). While progress has been achieved in recent years, there is evidence that only a fraction of real incomes is declared.9 A fully collected income tax could raise an extra 2-4% GDP, depending on whether the informal sector is considered or not. Banking secrecy has also been a main obstacle to the collection of the tax on capital gains earned abroad by tax residents in Lebanon, leading to the loss of another important source of revenue.

capital is under-taxed. First, bank secrecy prohibits effective control on the bank accounts that are transferred to heirs, which remove an important deterrent to the non-payment of the inheritance tax.10 Second, the tax code provides a tax exemption of capital gains when transferring shares in Lebanese joint stock companies, which leads to huge amount of tax avoidance and abuse, notably in the real estate sector.11 Third, the Lebanese offshore company has become an important vehicle for taxevasion. Fourth, interest, dividends, and capital gains earnings made abroad by Lebanese residents, which are legally subject to domestic taxation, are practically not collected at all. The same applies for inheritance taxes on foreign assets owned by Lebanese residents. Finally, disguised donations are also a widely used loophole.12 As a result, a host of reforms are needed, on the text of the law, and in its application, to improve the collection of taxes on inheritance, and more generally, on capital.

Beside their large size, these leakages have a regressive nature. Direct taxes are more rigorously assessed for taxpayers at the bottom (coming from labor wages) than at the top (coming for the income of liberal professions) of the income distribution. Tax avoidance is easier for richer taxpayers, since fiscal rules contain several deductions and exemptions (see section 5), and the bank secrecy law impedes access to information about assets held more by well-off taxpayers.

An unequal country

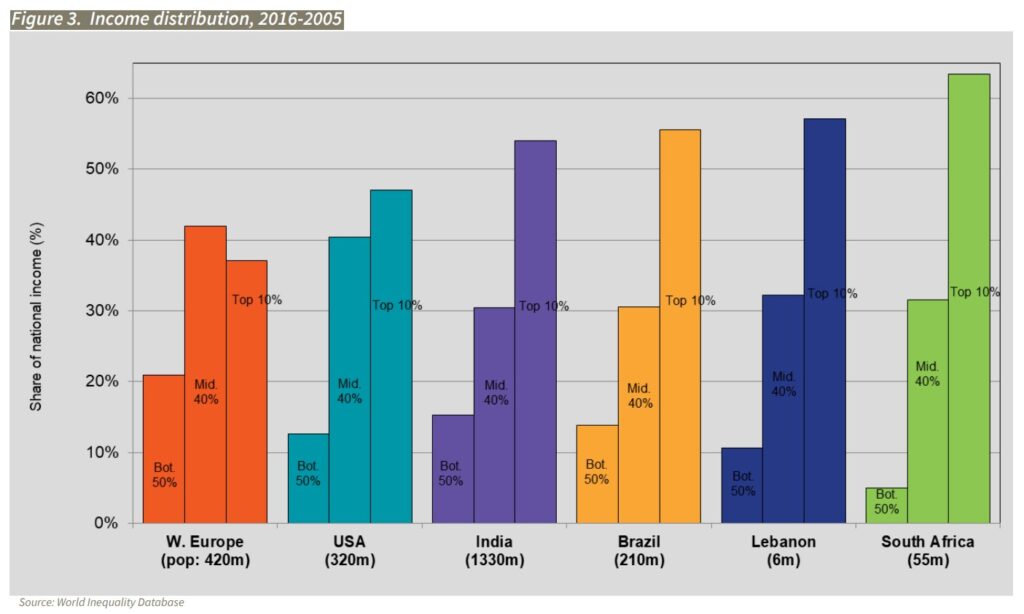

That the tax system is un-equalizing is an especially important issue in Lebanon because it is a highly unequal country. A large body of research has shown income is extremely concentrated. For example, the World Inequality Database reveals that around 2015, the top 10% individuals earned 54% of national income, the middle 40% received 34%, and the poorest half of the population received only 12 % (Figure 3). This level of inequality is among the highest in the world, more than in Brazil, and approaching South Africa levels. Although even harder to estimate, wealth inequality also appears to be extreme, as reflected in the highly unequal distribution of bank deposits.

The 2019-2020 economic and then COVID-19 crises and the Beirut blast have led to an economic collapse of historic proportions: unemployment has shot up to 35-40% as many firms had to close. Rising inflation has led to a collapse of real wages. The freezing of bank accounts has led at the same time to a further impoverishment of the middle class. As a result, poverty rates are estimated to have jumped from 15% in 2018 to 45% in 2020, extreme poverty has risen, and the middle class is at risk of disappearing.

Tax Reforms for more Social Justice

The conclusions of the discussion so far are clear: the tax system in Lebanon does not raise sufficient resources, both because of the way it is structured and because it is excessively leaky, and it is moreover un-equalizing. Based on this diagnostic, we develop our recommendations, in the rest of the paper, along four categories: (i) make tax incidence more progressive; (ii) reform further tax management to enlarge the tax base, with a systematic fight against tax evasion and tax avoidance; (iii) start aligning the tax system with measures to improve the social good; and (iv) consider a one-off wealth tax as one element of a mix that will help resolve the current crisis in a socially fair manner

3. SHORT-TERM CHALLENGES

In the short term, there is an imperative of stabilization, which will have to include a reduction in the fiscal deficit as part of a comprehensive plan that include fiscal reforms, debt reduction and bank sector restructuring as well.14 Austerity measures will be especially difficult, and socially divisive, given the depth of the current recession and the impoverishment of the middle class. There will be choices to make on how to balance the fiscal effort between expenditure cuts and revenue increases, and also on how to increase revenues – how much to raise tax rates vs. how to enlarge the tax base. All these decisions have distributional and efficiency implications, and they are also unlikely to be accepted unless trust between citizens and the state is rebuilt, which will not happen without important political reforms.

How have revenues reacted to the crisis?

In 2019, until end July, tax revenue was LBP 8372 billion. For the same period in 2020, these dropped to LBP billion 6075 (-27.4%), due to the deep recession, but also to the measures related to COVID-19, which allowed taxpayers to differ their payments (until mid-2021).

This reduction reflected differential performance of different tax instruments. Revenue from income tax fell by 20.5%, broadly in line with the fall in GDP. VAT dropped by 55.2% (from billion LBP 2235b to 1001b), and customs and excise fell by 33% (from billion LBP 1129b to 756b). The massive reduction in customs and VAT reflects the huge reduction in imports since the eruption of the crisis. That the VAT fell more than customs reflects a larger drop in its internally collected part, as the government allowed delays in payment to offset the Covid-19 shock.15 Tax revenue on interest income rose marginally – the increased rate to 10% compensating the fall in interest rates. Tax revenue from corporate profits collapsed (from LBP 1316 billion in January-August 2019 to 241b in 2020), because of the deep recession and of measures to defer payment. Non-tax revenue followed a similar path, falling by 34.3% (from billion LBP 1695 to 1113).

How big is the primary fiscal deficit?

The primary fiscal deficit (which is the deficit before payment of interest on public debt) strongly deteriorated from a small surplus of LBP +870b to a deficit of LBP 1066b at end July 2020. MoF estimates that interest payments were about LBP 1966b (down from LBP4321b), implying that the overall deficit that would need to be financed in 2020 is around LBP 3000b, nearly half its 2019 level.

As for the expenditure structure, an even larger share is spent on salaries, even though real wages have collapsed given the very high rate of inflation (about 120% for 2020), suggesting that wage adjustments will be necessary in the near term.

Given the enormous current volatility, it is difficult to express fiscal data in terms of shares of GDP. What is clear however, given that inflation in 2020 is running very high, is that the GDP denominator has risen enormously (in nominal terms), while tax revenues have fallen, and expenditures have remained nominally broadly constant (except for interest payments). This then suggests that both expenditures and revenues have sharply fallen as a share of GDP. Recent estimates by MoF and the World Bank for 2020 are that expenditures fell to 17.3% GDP, total revenues to 11.5% GDP, the primary deficit stood at -3.6% GDP (from +0.7% GDP in 2019), and the total deficit at -5.9% GDP (from -10.6% GDP in 2019). This is however a transitory situation. As some government expenditures will get (at least partially) adjusted to inflation, while many elements of tax revenues will not (see below), the fiscal deficit is likely to rise in the near term in the absence of policy adjustments.

No-adjustment scenario

The way in which the current macroeconomic crisis is resolved risks increasing dramatically the already high levels of inequality. The huge financial losses that need to be absorbed for the country to regain creditworthiness, and the banking system to regain its solvency, are estimated at about $60 billion (about twice current GDP).16 While there has been no single government action to help resolve the crisis since it erupted, with not even a capital control law in place, the strategy of doing nothing amounts to an implicit strategy that protects the capital-rich and the banks. On the debt and banking side, the current “liralisation” strategy is throwing billions of dollars of losses on the shoulders of the middle class. 17 In parallel the financing of the fiscal deficit through the inflation tax is eroding rapidly real wages and the value of LBPdenominated debt. In other countries that have experienced prolonged crises, similar cycles of inflation-financed-deficits followed by partial wage adjustments have lasted for years, leading to a decade of lost growth, and leaving deep scars in society and the economy. In contrast, in order to produce a fair and more efficient sharing of the burden of adjustment, losses in the banking sector should be allocated disproportionally to big accounts.

How much additional revenue in the short term?

For a more favorable adjustment scenario to take hold, as part of an overall recovery plan, the fiscal deficit would have to shrink. Faced with a decline of GDP in 2020 estimated at over 20%, Keynesian logic would call for an expansion of government expenditure. In the case of Lebanon however, this cannot be done. The state is in default, mired in an enormous debt overhang (with total public debt to GDP, including the losses of the central bank, now estimated at over 300%), and it cannot presently borrow at any interest rate. Instead, fiscal consolidation is needed to get growth going again, as part of a package of reforms whose aim is to allow the state to regain its creditworthiness (through debt reduction), and the banking system its solvency (though a bailin).18 In the current circumstances, the only way to finance a fiscal deficit, while still reducing inflation, is through resorting to new international borrowing from senior creditors such as the IMF. In such a scenario, the main trade-off is between the speed at which the fiscal deficit is reduced, and the amount of debt reduction: in particular, deeper debt reduction would create some fiscal space that would allow for a slower adjustment of fiscal accounts, financed by new public debt.

A reasonable target, in our view would be to gradually stabilize and then eliminate the primary deficit over a period of 3-5 years. The next question is about how to balance this effort between spending cuts and revenues increases. This is a standard issue during adjustment. International evidence suggests that when austerity measures are necessary, cutting expenditures rather than raising taxes is more helpful for a recovery, as multipliers tend to be more favorable.19 We find the argument especially relevant for Lebanon, as a large part of expenditures is not particularly productive. A big effort is long overdue on transfers (especially to EDL), on the size of the public sector (as opposed to real wages), and especially on the totally unproductive “political spending”. The level of several types of expenditures (e.g., some of the pension schemes) will also have to adjust to the lower standards of living of post-crisis Lebanon. Because new types of expenditures are urgently needed (especially a social safety net), these cuts need to be deep early on to open fiscal space. Moreover, it is unlikely that the population will accept a larger burden of taxation until the adjustment effort gains in credibility, and it starts seeing improvements in the quality of expenditures.

In developing revenue targets for the medium term, it is important to realize that the structural changes introduced by the current crisis result in lower tax revenues if current tax rates remain unchanged. While the current drop in revenue is partly due to the deep recession and to Covid19, it is also related to the steep reduction in import and in interest earning, which have each been cut by about half. In the medium term, both imports and interest earning are not expected to recover to previous levels. The shortfall in tax revenues can be estimated at about 3% GDP. It should also be noted that the heavy reliance on revenues from telecoms (tax and profits) leads to high telecom prices, which imposes a heavy burden on high-tech-led growth, an area where Lebanon has a relatively high comparative advantage. It will be necessary in the future to reduce the reliance on raising revenues from the telecom sector to improve the competitiveness of the service sector.20 This would create an extra shortfall in revenue that needs to be compensated by other taxes.

Our recommendation then is for revenues to rise gradually over time so they can regain their 2018 level (15% GDP) in 4 years. This fiscal effort amounts to 4-5% GDP, and is thus ambitious, albeit necessary. This goal will require new revenues to compensate for the structural fall in VAT, customs, and taxes on interest revenues caused by the demise of the old economic model based on imports and high interest rates. After the adjustment period, and once expenditures have been rationalized (and reduced), both expenditures and revenues can rise again, with the goal of reaching levels more commensurate with Lebanon’s aspiration for a fair and efficient society – around 20-25% GDP in tax revenues and in expenditures.

More revenue and more equity

How to raise revenues? Where the IMF typically believes that quick money needs to come from a massive increase in VAT rates, we do not favor this solution.21 As discussed earlier, taxes tend to fall at the moment largely on the poor and the middle class, and expanding them would be not only unfair, but would also lead to a large further contraction of demand, and thus of the economy. Thus, reforms that shift the burden of taxation towards the richer in society are needed as the same time as tax revenues are increased, so that the tax structure becomes progressively fairer at the same time as the economy is stabilized.

We estimate that about half of the needed increase in tax revenues can come from improving compliance. The largest areas where this seems possible in the short term are from taxes collected at the border (VAT and customs), and taxes on revenue (individuals and firms) – which we estimate together at +2% GDP. The customs administration will have to become more disciplined in collecting revenue at all borders.22 A rationalization of the scope of the VAT to all the products that are not of basic necessity so as to make it even more progressive than it currently is, could increase VAT revenues by an additional 0.5% GDP. A tighter collection of the income tax is also necessary.

In addition, taxing capital held by Lebanese resident abroad has become possible, given the recently established exchange of information agreements between Lebanon and a multitude of countries in the context of the OCDE-G20 Global Forum. Although it is hard to estimate what can be collected given the dearth of information on the size of Lebanese residents’ capital abroad, this is a crucial issue in the tax reform package. Besides raising additional revenue, improving tax collection from large incomes and starting to collect taxes on capital abroad will send the important signal that taxes have started becoming more progressive, thus improving the willingness of all citizens to pay their taxes. How to improve revenues from income and corporate taxes is discussed below.

4. TOWARDS MORE EQUITABLE AND EFFICIENT TAXATION

Reforming the tax system is an old topic in Lebanon. There have been many proposals, but these have faced with strong opposition from the economic and political elites. Our main proposal is to deeply reform the Personal Income Tax system by moving to a general income tax system that taxes all sources of income together (“the whole of revenue”), and not separately as in the current system, and that has a much higher level of progressivity. We also examine in the next sections how to reorganize exemptions in ways to promote the public good, and how to broaden the tax base by fighting fraud and tax evasion.

Taxing “the whole of revenue”

In order to apply the principle of progressive taxation, it is centrally important to move away from the current system where different types of incomes are treated separately, and to institute instead the concept of “the whole of revenue”, which incorporates in the individual taxable income base all types of revenues, from wages and salaries, to capital gains, dividends, interests, property and land incomes, commercial and professional revenues, and the international capital income earned by residents. Such a reform entails an ambitious tax harmonization effort through the regrouping of disparate fiscal provisions in a General Tax Code.23

Within that plan, our proposal is to increase the marginal tax rate on the whole of income to at least 30-40% on the top range of incomes. Such rates remain below international rates and should not act as a disincentive for highly skilled Lebanese to retain their residence and work in Lebanon.

How about corporate tax?

At 17% currently, the corporate income tax is low in Lebanon. Driven by tax competition, corporate tax rates have fallen globally, and now stand at around 20% in many countries. This has contributed to corporate tax base erosion and the increasing trend in income inequality in many regions of the world.24 There is an ongoing global effort to establish a minimum level of corporate tax at around 20-25%.25 However, since the main goal over the medium-term in Lebanon will be to promote private investment, an increase in taxes on business should be carefully timed. At the same time, tax provisions promoting particular types of investments would be needed initially, although these have to be managed for performance, and not driven by rent seeking (see next section).

Property tax

The tax to rental income is progressive (4 to 14%) but below rates at which wages are taxed. Until rental income becomes part of a whole of income system, these tax rates need to converge. We also propose to apply a larger rate on empty and vacant property, to stimulate their use for productive activities, as done in many countries.

Taxes on capital income

In case moving to a whole of income tax is delayed, we propose in the interim, to increase the tax rates on the various parts of income, and especially those that tax the return to capital, so they become harmonious with the taxation of labor income, both in their rates and their progressivity. In particular, we propose moving rapidly to tax property rental, interest, and dividends revenue at levels similar to what labor income pays. This would over time help rehabilitate the value of hard work compared to rent income.

Inheritance tax

Lebanon is an exception in the region, and has an inheritance tax. It is however poorly collected. A wholesale revision of the inheritance and gift taxes’ law is needed to address massive loopholes that allow individuals to pay much lower effective rates through various mechanisms, including tax-exempt vehicles and the use of disguised donations.

A wealth tax?

There has been in recent time widespread calls for taxing wealth, given the very high level of wealth inequality in the country. There are proposals for a one-off tax on wealth as part of a stabilization package to resolve the fiscal-cum-banking crisis, in addition to efforts to reclaim illegally accumulated wealth. In the medium term, once the economy is stabilized and losses have been properly assessed, a regular progressive wealth tax should be considered. The economic justification, besides improving revenues, is to reduce inter-generational inequality.

Municipal revenues

Revenues accruing to municipalities now come mainly from transfers from the treasury, in the form of shares in the various taxes collected – about 10% of most taxes. At minimum, the system of tax sharing will need to be adapted to the proposed reforms on taxing whole of income. It would be moreover important to review the sharing formulae. Municipalities receive a quota based on the number of people registered in their constituencies. This benefits large cities, who now get most of the revenues, irrespective of real needs, but it is detrimental to small municipalities that have many of their inhabitants registered elsewhere. In addition, in many municipalities, waste management costs are directly deducted from their share, leaving them with very little resource. Some taxes, such as the built property tax, could be collected directly at the local level, to reduce corruption, and to lessen the dependence of municipalities on the central government (the losses to the Treasury would be compensated by reducing their transfers to local authorities accordingly).

VAT

At 11%, the VAT rate is not overly large in Lebanon compared to the rest of the world. What is large is the proportion of tax revenue derived from regressive indirect taxes. But it is only in the context of an overall reorganization of the tax system in ways that makes it more progressive, and with the goal of collecting closer to 20% GDP in tax revenues – that there would be room to moderately increase the rate of VAT in the outer years.

Diaspora concerns

Many citizens in Lebanon are foot-lose, including among the highskill category, living and working between the homeland and the Gulf or Europe in particular. Providing them with incentives to reside and pay taxes in Lebanon, and more broadly, to base the core of their activities in Lebanon (especially in the creative and high-tech industries and services) is an important goal. The manner of determining taxes of residents on incomes earned abroad, in the current “territorial regime”, is dependent on the nature of income: financial income (on “movable property”) is taxed where the beneficiary resides; income derived from the performance of services, and from real estate, where the services are performed and where the property is located. Thus, for footlose residents, tax rates on income and capital matter in deciding where to locate their residency. While taxes are starting to rise in the GCC, for the foreseeable future, the main advantage that Lebanon can deploy relates to better living conditions. Compared to Europe, Lebanon will need to continue to tax less, but this leaves considerable room to increase tax burdens.

The new challenge of digital technologies

The world is becoming digital. This presents an opportunity to combat tax and evasion. But this also creates new risks of tax evasion, as the growth of electronic commerce and the transformation of business models are creating unfair competition between local operators and multinational digital firms (such as GAFAM, Uber, Airbnb). Both indirect and direct taxation are affected. The ability of multinational enterprises to create complex corporate structures and use transfer pricing to their advantage allow them to shift profit to low tax locations. The main global initiatives to fight base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) is an effort headed by the G20 and housed in the OECD that proposes that profit be taxed where economic activities that generates it is performed. While Lebanon should join this initiative,28 it could, in the meantime, proceed on a stand-alone but concerted manner (like India or the UK), by combining consumers’ and operational geography factors (for example to the operations of Airbnb, Uber, Amazon).

5.TAX INCENTIVES AND DISINCENTIVES:

Insufficifrom counterproductive to socially useful

Tax incentives can be a useful tool to encourage specific economic activities and promote underdeveloped geographical areas. It has also been used in many countries to attract FDI, although the current leading view is that a good business climate and the presence of skills and infrastructure are more important than taxcuts in attracting investment.

While tax breaks have been provided widely, from a social good perspective, most of the existing tax incentives are outdated, and in many cases, used in a manner that allow privileged taxpayer to abuse the spirit of the law. It is not surprising therefore that tax expenditures are poorly measured and not evaluated. At institutional level, best practice requires treating tax reduction granted for economic and social purposes in the same way as budgetary expenditures: they must be measured, reported, evaluated, and controlled. None of this is done systematically in Lebanon. For example, in 2018-19, Parliament cancelled penalties on unpaid taxes and decreased registration fees on residential properties. But there was no estimation of cost and benefit – in fact, no justification at all offered in the budget document. 29 To guard against rent seeking, a prior impact study of all exemptions is needed, and regular monitoring of effectiveness in reaching social and economic goals must be required.

Existing tax incentives with dubious benefits

Most existing exemptions are counterproductive from a social and economic perspective, and have been put in place as a result of rent-seeking, as opposed to meaningful economic arguments. Below is a select list.

Real estate activities. Policies meant to stimulate real estate activity (including reducing the registration and transfer duties, eliminating the capital gains tax, and creating VAT exemptions) have led to an over-supply of properties. While the sector has been an engine of economic growth and job creation during the last two decades, this type of growth crowded out capital that could have gone to more productive and sustainable sectors. Indeed, the real estate sector collapsed during the current crisis, with a massive oversupply at the higher end of the market.

Education. All educational institutions have been exempted from income tax since 1959. This was originally intended to combat illiteracy. But more recently, the exemption has given rise to the growth of a highly profitable sector, which operates without any quality control, leading to the proliferation of low quality commercial public school and universities. More generally, public sector entities, NGOs, religious orders, some public employees (military, judges) are exempt for many taxes. While there are good reasons to exempt social services from taxes, the system should be tightly controlled to avoid misuse, such as the overpayment of wages to insiders, or the pursuit of commercial goals under the cover of a non-profit.

Finance. There are several types of exemption, initially introduced for the purpose of attracting FDI, which have been heavily abused. The tax exemption on transfers of shares in Lebanese joint stock companies leads to huge amount of tax avoidance and abuse, notably in the real estate sector, reducing capital gains and inheritance taxes. Second. Investment banks have been totally exempt from the corporate taxation during the first seven financial years of operation, and up to a ceiling of 4% of the bank’s paid-up capital afterwards. This can also be misused by banks that manage, through creative accounting, to tunnel part of the profit of their normal operations to their investment branch.

Offshore companies, and their shareholders, are exempted from both the corporate income tax (17%), and from taxes on capital gains, on distributed dividends (10%) as well as on inheritance of shares.31 Created in 1983, these exemptions were meant to attract companies active in the MENA region to use Lebanon as a major center and to encourage the production at home for goods, and especially services for export and technology markets. There are two separate issues. First, the tax advantages provided to offshore companies need to be re-evaluated, to find the right balance: encouraging exports is an essential goal for the future, but production for export uses public goods. Second, these exemptions must be carefully monitored to ensure that they are not misused for profit optimization.

Agriculture. The deplorable situation of the agricultural sector, with production now at about 4% of the GDP, has created a concentration of poverty in rural areas. To reduce poverty and sustain unfair global competition, larger exemptions seem justifiable. But these need to be regulated much better that the current agricultural subsidies (tobacco, sugar).

Industry. Industrial companies established in particular regions have been exempted from taxes for a period of ten years (specially, in industrial parks created in the districts of Nabatiyye, Jbeil, and Zahleh). It is not clear how the regions and the industries have been chosen, and how efficient this exemption has been. On the other hand, another more wholesale FDI promotion mechanism, under IDAL, has been misused to lower tax burden. IDAL’s beneficiaries are practically always large and well-connected investors competing with normal investors – their particularity has been their ability to have their exemptions approved by cabinet.

Well-targeted tax incentives

On the other hand, there is a dearth of incentives that serve useful economic and social purposes, and these need to be built in the system in the future in order to achieve accepted national goals. Introducing new taxes on activities that are harmful to health and/or prejudicial to the environment (such as quarries and cement factories) have become popular demands by environmental groups and associations. Such tax revenues can also be earmarked to the same causes. While in general frowned on, because earmarking restricts budget flexibility, they have the advantage of unleashing social vigilance for effective collection. For example, the creation of a special fund to promote natural habitats through taxing stone quarries increases environmentalist groups’ efforts to ensure that rules are applied.

When the goal of such incentives is to create jobs, interventions will need to be developed and managed as part of a well-thoughtout industrial strategy. To encourage innovation, skill-upgrading, and risky investments, instruments such as tax-breaks for infant industries, subsidies for R+D, the creation of free-zones, growth poles, incubators (with agglomeration effects, low taxation, and more effective public services), support for private sectoruniversities linkages have been widely used in other emerging markets, and should be emulated in Lebanon as it seeks a new growth path in the future.

6. COMBATING TAX EVASION AND AVOIDANCE

The tax base needs to expand considerably toward the richest in society, as all reports suggest that compliance is extremely low for the wealthiest. In parallel, efforts should continue to educate small taxpayers so as to improve compliance.

Mobilizing revenues more efficiently involves modifying taxpayers’ behavior, and this requires efforts on three dimensions: the provision of knowledge and information, reforms to improve the rule of law, and more fundamentally, a rise in confidence in the state, which requires progress on its effectiveness and fairness.

There are several reasons for the current state of affairs. First, low taxation is a reflection of the neo-liberal economic regime put together after the civil war. A second factor is the poor application of rules, due to rent-seeking behavior. A third factor is that attempts at modernizing the system were systematically blocked by politicians to defend their short-term interests and that of their business partners.

In spite of these headwinds however, several reforms have been attempted in the post-civil war period, and some progress has been achieved. These efforts are a testimony to the remaining meritocratic culture still present in some parts of the administration, and also, of occasional helpful support by international organizations in the form of technical assistance and pressure to implement change in return for aid. While many efforts have failed to fully deliver on their promise, some did lay the groundwork for the reforms proposed in this paper.

Digitize, and expand the information base

Besides tackling the existing loopholes in the current tax system, there is an acute need to modernize the whole management of tax administration. This starts with the broadening the tax identification number to all residents.33 Digitalization helps in combating tax evasion and broadening the tax base by allowing the aggregation of taxpayers’ data from a variety of sources. Data from the VAT in particular allows triangulation with customs and corporate data for better compliance. The information gathering effort has improved between 2009 and 2015, after enormous resistance. The MoF can now obtain online information from customs, the cadaster, and social security. Special applications already help detect fraudulent behavior by importers at the border. Digitalization can also be of great value in the enforcement of property taxes through the use of electronic maps that facilitate the identification of unregistered properties to update the property cadasters, and by analyzing real estate transaction data to determine the fair value of properties. The use of big data and search algorithms can also allow for a better tracking of shell companies registered in offshore jurisdictions.

Simplify to tighten regulations

Simpler regulations foster accountability. The Ministry of Finance has already developed a full system of e-taxation, e-declaration, e-payment, and a well-performing mobile application for taxpayers. The use of cash was eliminated, to reduce corruption, and citizens were given a menu of financial avenues to settle their tax dues. A “whole of income” tax reform will replace over five tax forms with a single one, greatly simplifying procedures. Reducing exceptions, fairer procedures, and efficient processes for conflicts resolution also reduce the likelihood of tax disputes. In particular, simplification reduces the scope for tax avoidance, which is the legal practice of minimizing a tax bill by taking advantage of loopholes and exception, or adopting an unintended interpretation of the tax code.

Banking secrecy

The elephant in the room is banking secrecy. As the world become more transparent, there is no room for tax heavens in the future, and in any case, the Lebanese banking system has irremediably lost its reputation as a safe haven. As a result, banking secrecy is not useful anymore in making Lebanon more attractive. In the future, capital will be attracted by growth opportunities rather than low tax rates. The cost of banking secrecy is very high from a tax compliance perspective – it is obviously bad for income tax (independent professions), the inheritance tax, and capital invested abroad. It is hard to imagine a workable tax system, and much less a cleaning up of the banking system, unless bank secrecy is abolished.

International cooperation and exchange of tax information

The completion of the automatic exchange of tax information system that Lebanon joined in 2009 is an area of great importance. As previously stated, the efforts of the general directorate of Finance have brought Lebanon to become a “largely compliant” country with regards to tax transparency and exchange of information. This means that the Lebanese tax authorities will be able to automatically get all information regarding capital gains and interests earned in most of the world by local residents, and thus collect taxes on this income in accordance with Lebanese law. But while Lebanon is on the cusp of eligibility to start receiving tax-related information from other countries, it must implement a few remaining steps to secure data confidentiality.34 Until this is done, Lebanon is in the surrealistic position where it provides banking information to the world (but not to its own administration!), while refusing to receive the same information from counterparts! The completion of the process would allow the MoF to receive valuable information on assets/securities (financial assets) held by its tax residents abroad. There is an urgent need to move on this front, especially that this source of income has not suffered from the recent catastrophic monetary and banking developments in Lebanon.

Informality

The informal sector is estimated to account for 36.4% of GDP, and 67% of the workforce in 2015. Many of the informal firms are low-skilled self-employed poor individuals, involved in lowproductivity activities. In their case, public policy needs to focus on actions to reduce inter-generatonal poverty by supporting education and heath, and access to training and micro-finance. But there are also many firms that are large enough not to be informal, but that avoid formalisation in order to save on taxes and regulations. These firms not only reduce fiscal revenues, but they also compete unfairly in their markets,underpay their employees by not enrolling them in the social secufity system, and risk the health of citizens by not being subject to quality and environmental controls. Both sticks and carrots are needed to push them into the formal system.

Sticks and carrots

Rules and regulations should adequately sanction all perpetrators and enablers of illicit tax practices (tax evasion, tax avoidance and money laundering) or turn a blind eye to them. But currently, there is no stick in the legal framework. If a taxpayer doesn’t pay, not much can be done to enforce payment.35 Soft compliance measures can be more effective when sticks exist, such as friendly tax controllers’ visits to help taxpayers avoid penalties. Since 2004, MoF has started moving from a narrow audit-based approach to one based on risk and compliance. Specialized offices for compliance, audit, and customer services were introduced in 2005 with the stated goal of servicing customers better. The number of audits has already risen four-fold since 2002. Greater effort is still needed to be able to distinguish between firms that are fleeing taxes, and those making real losses.

The lack of cooperation by political parties and Parliament has been a major constraint to ensuring compliance in the past. Until recently, the Social Security Fund, customs, municipalities, or the security forces, have refused to provide the tax administration with timely information, and Parliament has resisted passing compliance measures. Regularization (amnesty) has been repeatedly offered in the past. This has by now greatly reduced the credibility of sanctions, and should thus be only used sparingly in the future.

Moreover, for checks and balances to work, the administration should not be judge and party at the same time – entitled to elaborate the texts, apply them, and control performance, as it is currently the case. Disciplinary sanctions should apply in much more credible ways to officers who fail act professionally. Good governance in tax collection must rest on the promotion of transparency and accountability, a clear ethically based code of conduct (including income and asset declaration of public officials); and the promotion of the rule of law and an effective sanctions regime.

More important than sticks however is the challenge of strengthening fiscal citizenship. To do so, public authorities need to change the reality and perceptions regarding the fairness of taxation, and empower tax-paying citizens as the pulsing heart of the democratic social contract.36 As part of the effort, they must disseminate more information about the tax system to the public, simplify tax regulations and procedures, and promote transparency and accountability in the national budget.

5.CONCLUSION:

BUILDING POLITICAL SUPPORT FOR FISCAL REFORMS

The past performance of the tax system illustrates the paradox of a dominating but weak political regime: a large appetite by politicians for rents to distribute to their clients to secure their power, but a relatively low level of state revenues due to low taxes on top incomes, capital, and wealth. The implied constraint on “milking the state” has pushed the political elite to monopolize large tracks of the private sector, where the dominance of “crony firms” has made Lebanon a place inhospitable to wealth-creating businesses.38 The current debt and financial crisis is a direct result of this paradox. Moreover, the power sharing system among sectarian groups has neutralized the ability of the political system (dubbed a vetocracy) to reach principled decisions that require short-term sacrifice for the general public good.

Rebuilding the tax base on the principles of efficiency and fairness is a central part of both the ability to respond to the current financial crisis, and to create a dynamic and sustainable growth path. This type of wholesale policy reforms however requires political courage, and the support of a population that trusts its government. These ingredients are unfortunately not available now. On the other hand, a credible and reformist government will find plenty of space for progress. While there is typically a trade-off between social fairness and economic efficiency, such a dilemma is less marked in Lebanon. The tax structure of the recent past has been so inefficient that tax instruments can be devised to raise considerably more funds without reducing the incentives for wealth-production.

The fight for fiscal justice and effectiveness needs to become a more central part of political concerns in Lebanon. Indeed, a main reason why the needed economic reforms cannot proceed without political reforms is that taxation gets rejected when it does not come with adequate representation.